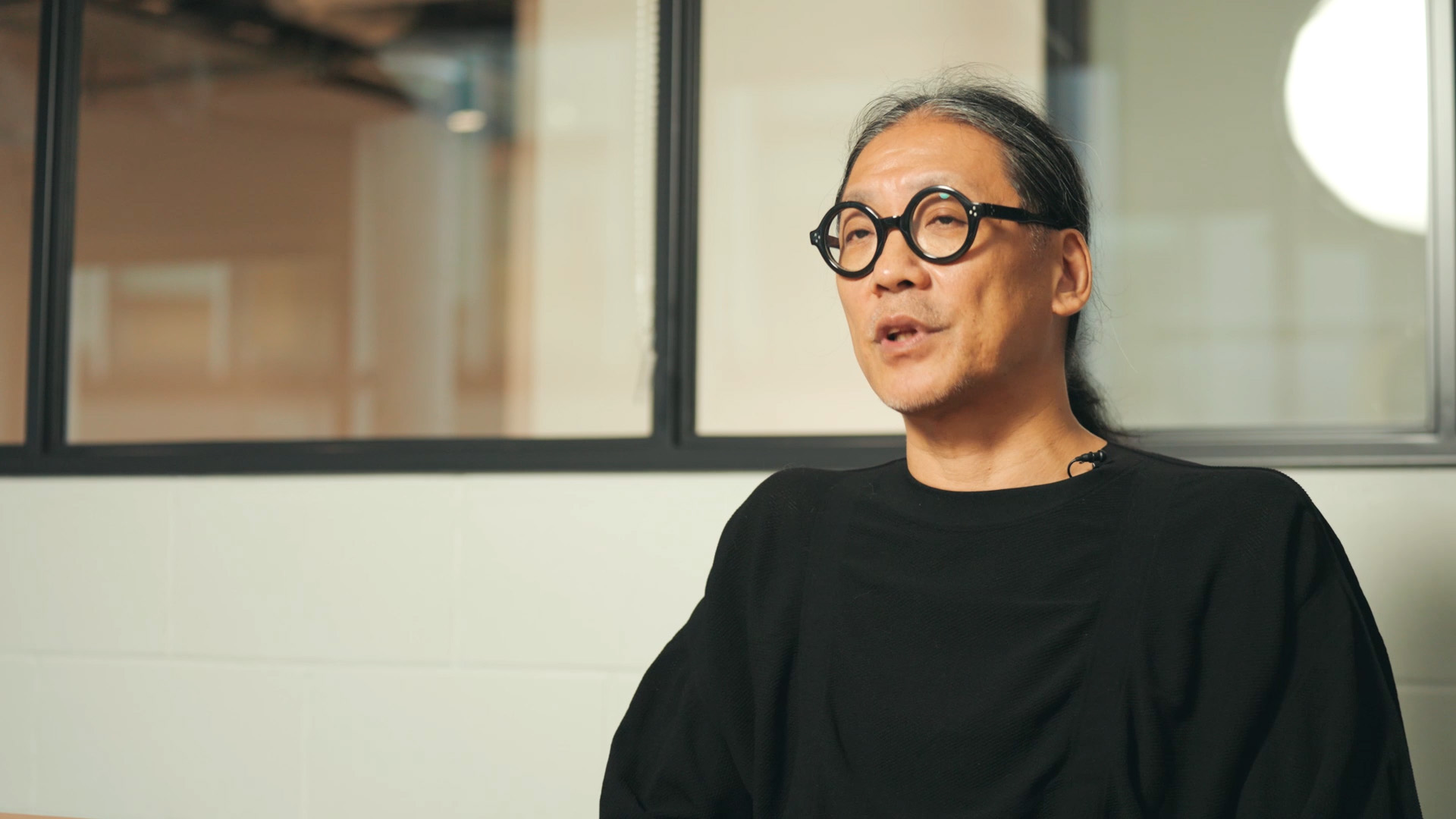

“Future of Life” Creator’s Voice Vol. 8, Spotlight on MATSUI Tatsuya – Androids/Robots Designer

Flower Robotics, Inc.

MATSUI Tatsuya

Current job responsibilities

As a designer and artist, I design robots, create contemporary artworks, and teach at universities.

Role in Future of Life/Responsibilities and duties at the Pavilion

My role was to take the many robots and androids conceptualized by Professor ISHIGURO Hiroshi’s team and give them both form and meaning, presenting what robots and androids of the future might look like in a way that befits the stage of the Expo. Specifically, I handled the overall design of several robots and androids: the monkey-shaped robots aiai, which greet visitors at the entrance; aiai walkie, encountered inside the exhibition rooms; the guiding robots Petra, Punica, and Pangie featured in ZONE 2; and the android Yoshinoroid, which appears at the end of the ZONE 2 exhibition. I also contributed to the design of MOMO, which represents humanity 1,000 years from now in ZONE 3, as well as Yui, who appears at the end of the exhibition.

Feelings on the Pavilion, the exhibits, and the product concept

Having worked with Professor Ishiguro for many years, I’m well aware of the consistency in his thinking as a scientist. I believe that unless a project’s core concept aligns with one’s own vision, it’s hard to create something truly meaningful. But I resonated with many aspects of Professor Ishiguro’s vision, so I wanted to embrace it fully and help bring it to life in tangible form.

Memorable impressions from associating with Producer ISHIGURO Hiroshi

Professor Ishiguro’s vision of using technology to explore what human dignity means in a time of profound societal and environmental change is, I believe, a theme that captures the interest of society as a whole, myself included. Among his ideas, the notion that “humans should be freed from all forms of constraint and become truly free” resonated deeply with me and profoundly stirred something in my creative self.

Commitments and challenges

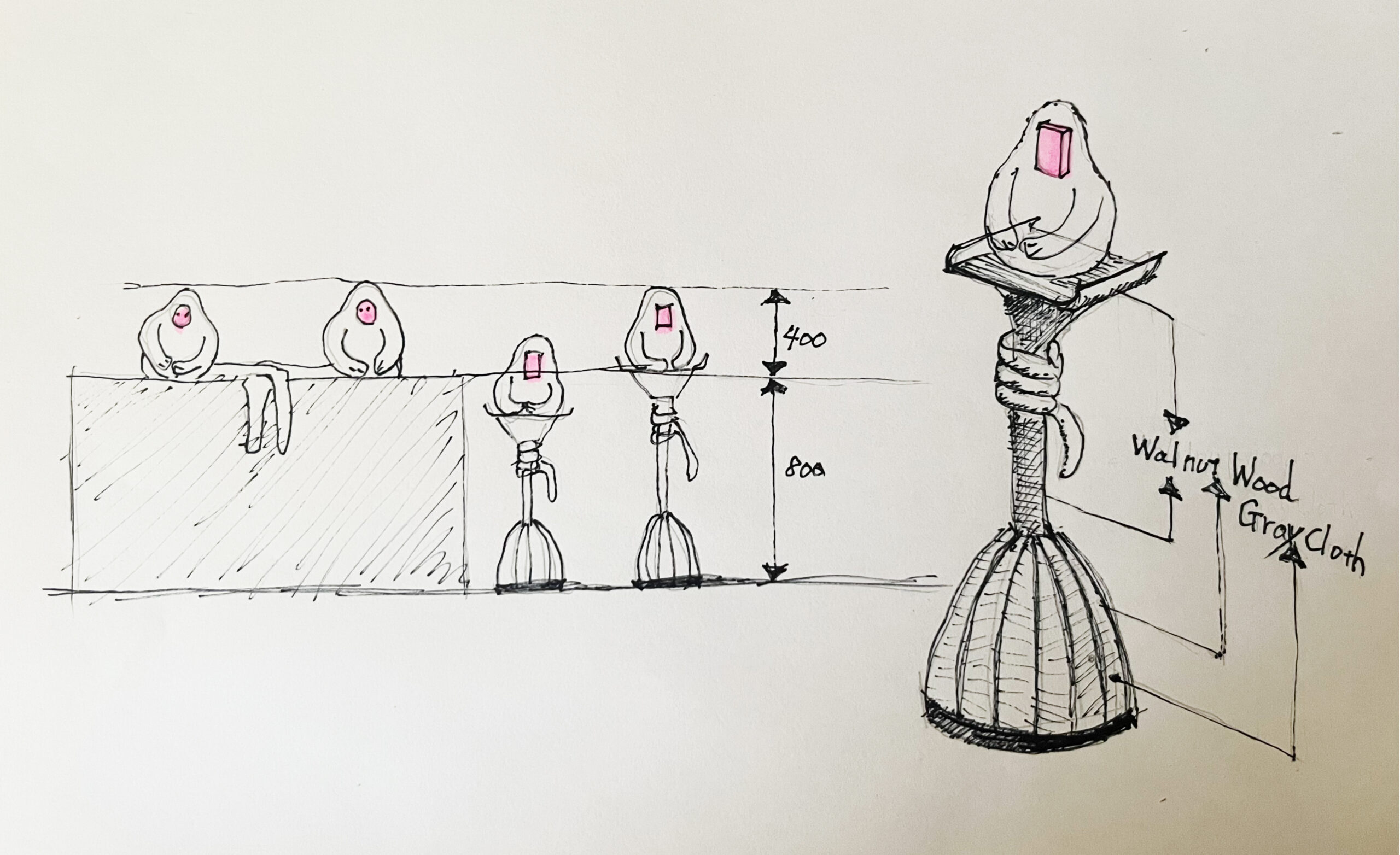

<aiai>

Quite some time ago, when robotic dogs first came onto the market, a manufacturer approached me to ask whether I’d be interested in helping conceptualize the next generation of robots. The saying “fighting like cats and dogs” has a Japanese equivalent involving dogs and monkeys, and I began to think that a monkey, an animal known for its intelligence, could make an interesting rival to a robotic dog. That led me to explore a monkey-inspired robot design. Ultimately, the idea was never realized, due in part to the fact that the concept I proposed was too ambitious, but even back then, I had already come up with the name “aiai.” Then, while we were discussing the robots for this Pavilion, I happened to visit the Great Buddha Hall of Todai-ji Temple in Nara, in connection with another project. At one point, I found myself completely alone there, with just me and the Daibutsu, the Great Buddha. In that moment, I suddenly pictured a monkey, like Sun Wukong, the Monkey King, softly floating through the air, and I thought, “Yes, this is the moment to finally set aiai free.” When I shared the idea with Professor Ishiguro, he agreed, and thus aiai was born. Japanese macaques, as you know, have pink faces. This inspired a consistent storyline in which the pink-faced macaque evolves into MOMO, the human of 1,000 years in the future.

<aiai walkie>

aiai rides a vehicle called “walkie” that moves freely in all directions, up, down, left, and right. The interface displayed on the screen is inspired by the symbolic design of Expo ’70 in Osaka. The wooden section that aiai rides may look handcrafted, but it was actually designed in 3D and precision-milled using the latest technology.

<Petra>

Since many of Professor Ishiguro’s robots are already well known, I felt it would be odd to present them unchanged in a world 50 years from now, so I began by reimagining new forms and appearances that would suit that future. I imagined a future where, instead of using mass-produced goods, individuals freely create their own objects using technologies like 3D printers, and perhaps even build robots from everyday materials like stone and wood. To evoke that theme, I used natural materials like stone and wood as motifs. Moss also grows on Petra. This is because I wanted people to feel a sense of incongruity: Why is moss growing on a robot? At the center of Petra’s stone head is a mirror interface inspired by the shinkyo, the sacred round mirror found in Shinto shrines. In this way, I incorporated subtle touches of Japanese tradition throughout the design.

<Punica and Pangie>

While Punica and Pangie share the same structural framework as Petra, their head designs are inherited from Deme, a robot featured at the Japan World Exposition Osaka 1970. I consider Deme to be Japan’s first true robot design, which is why I felt it should be carried forward in a pavilion dedicated to robots and androids. For those who know Deme, I hope they’ll feel that its legacy connects the past to the present and extends into the future, a vision that is uniquely fitting for a world expo.

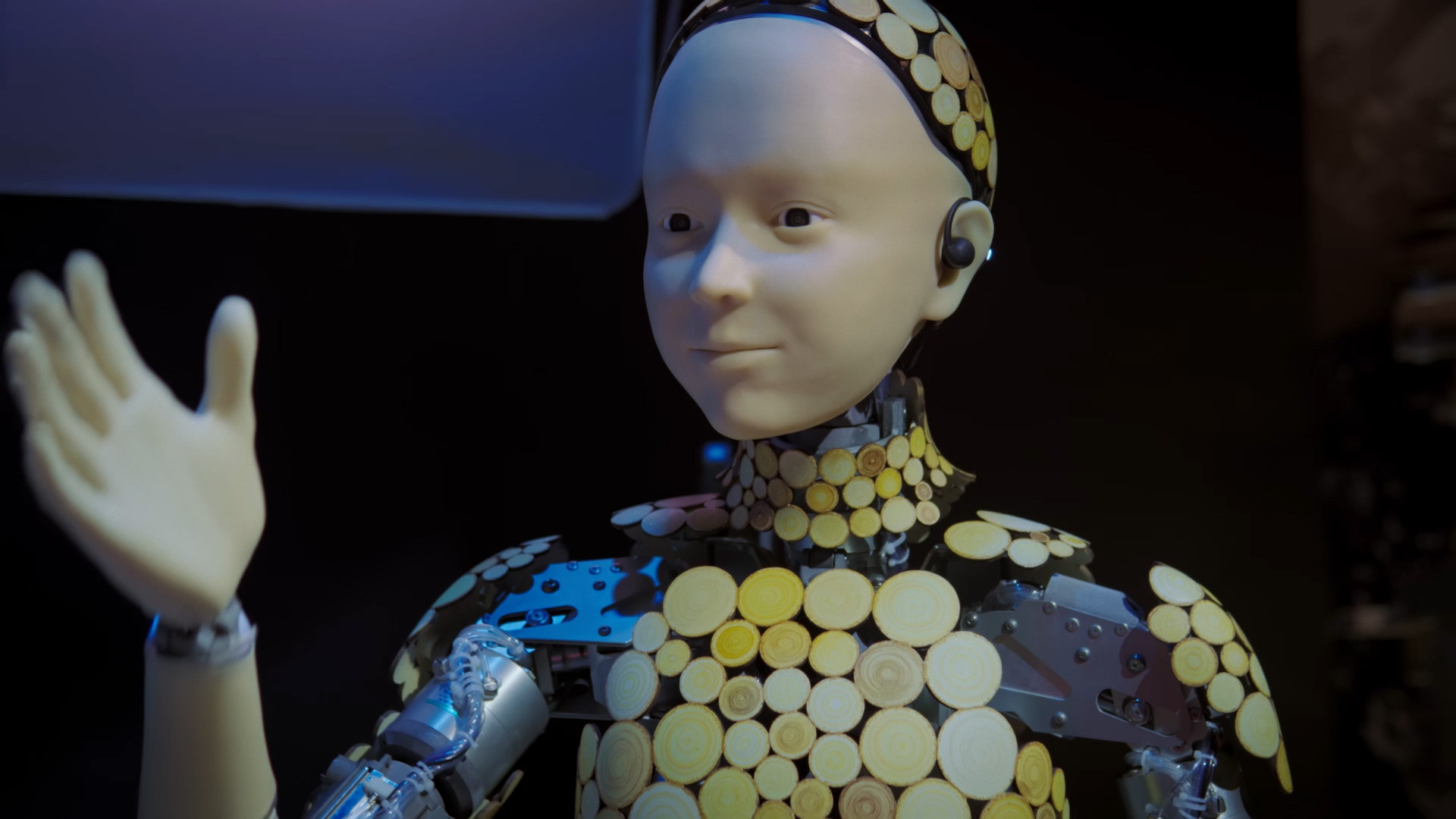

<Yoshinoroid>

We can reasonably expect androids fifty years from now to resemble humans so closely that, once dressed, they may be indistinguishable from us. With that in mind, I designed Yoshinoroid based on the idea that androids don’t need to mimic humans perfectly, and that there is value in exploring uniquely android forms of expression. Using a method called parametric design, I constructed a human form in three dimensions with the circle as the basic element, combining circles of various sizes and angles. Each part is not a flat piece like an Othello disk, but a complex, three-dimensionally fabricated structure. This idea stems from my belief that, in a future where generative AI continues to evolve, society will begin to question the very meaning of human thought. In that imagined future, I envision a revival of Wasan, Japan’s own form of mathematics, developed during the Edo period, as a form of intellectual play. Yoshinoroid’s design is based on the idea of applying Wasan’s circle-based methods of calculation in a three-dimensional context. The name “Yoshinoroid” was derived from the cherry trees of Yoshino in Nara Prefecture, a deeply evocative symbol in the Japanese imagination, which came up to me as an image as I was exploring design concepts. It connects directly to the cherry-blossom-colored space envisioned 1,000 years in the future.

<Yui>

The android Yui is a remotely operated avatar with highly expressive, humanlike facial capabilities. Because avatars represent a practical and socially significant technology, I approached Yui’s design as a straightforward expression of cutting-edge tech, positioning her as the “exit point” that connects the future, 1,000 years from now, back to the present. Instead of a wig, her head is designed using parametric geometry based on triangular forms, and 3D-printed into a sculptural shape that resembles hair. She wears a child-sized kimono with her hair styled in a traditional bun, embodying Japan’s spirit of omotenashi (gracious hospitality) and conveying a final “thank you” to visitors. The kimono itself is a custom-made piece of Kaga Yuzen, a traditional dyeing craft from Kanazawa. Parts of her head are finished in Wajima-nuri lacquerware, incorporating the aesthetic of traditional Japanese craftsmanship through red and black tones. While I was working on the androids’ design over the New Year holiday, the Noto Peninsula Earthquake struck. I felt that offering craftspeople in the affected region an opportunity to present their work on the Expo stage would be meaningful, so these collaborations came to life. As a result, Yui became a uniquely Japanese android blending traditional crafts, state-of-the-art technology, and mathematical design methods. I feel she embodies the android as “media”: a symbol of human hope and a bridge between society and emotion.

New discoveries and lessons learned

This project generated a wealth of bold, boundary-breaking ideas that overturned conventional notions of what robots are and opened up new possibilities for robots as a form of creative expression. I’d like to incorporate those ideas as variations in both the robots I’m designing now and those I’ll create in the future. I also made new discoveries with regard to design itself. Since the 20th century, design has always been closely intertwined with society and the economy. As a result, it’s easy to assume that future design is bound to emerge as an extension of our current society and economy. However, through this project, I came to realize that the future doesn’t necessarily lie along a straight line from the present, and that society could take shape in entirely different forms. I discovered that design can, and should, be considered from these kinds of alternative worldviews as well. That’s why I hope those involved in design will use this Pavilion and the Expo as a springboard to imagine futures that don’t simply extend from today’s society, and to explore what new forms of design could arise from those visions.

Highlights not to be missed

Everyone involved in this Pavilion engaged in deep discussions within the time available and poured all their energies into the work without holding back. I believe this project has reached one of the highest levels of expression of the future through the use of robots and androids in today’s world, and that every part of it is well worth seeing. Personally, I hope that visitors will feel through our many robots and androids that go beyond the typical mechanical look that design for the future can and should be free—and that they discover the potential of designs inspired by natural or animal motifs to help machines blend more easily into human life. Through design, I hope people will come away with the sense that the future is something each of us has the freedom to imagine and create for ourselves.